On paper, we live in a free and democratic society. Such freedom, we are told, was hard won. Our forefathers fought against fascism and other forms of totalitarianism, securing our rights as free thinking and self determining citizens.

In the abstract, all this sounds good, just and reasonable. Looking at western democracies through these lenses, however, ignores major parts of our lived experience, that might actually set us on an illusory path.

(1) On Liberal Democratic Societies: What is so often unsaid, is how political space is determined, We often view politics, as a legal/procedural area for (political) professionals. While we elect our politicians, we more than likely defer any serious political issues to those elected. We also ignore the fact that most people are now-a-days unelectable. Elected politicians must involve themselves in a process that means that they tow party politician lines. The majority of politicians are selected before they are elected. The free nature of enquiry is therefore already stifled, through a process of political distillation. Independent, free thinking politicians can be counted on one hand.

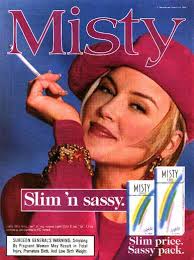

(2) On Living in a Free Society: While the thought of living in a totalitarian state sends shivers down my spine, we can not afford to be complacent. In areas such as gender politics, much is still to be done. This does not just mean putting more women into the board room. Women and men are influenced by societal norms that are not always questioned enough. A women’s right to explore her sexuality, for instance, is still a very difficult path to negotiate. Women have the right not to be treated as sexual objects by those who would also condemn them for making their own liberal sexual choices. Informally, we citizens are not as free as we might like to think, given the non-official pressures that we all face.

(3) On capitalist economics: Nation states compete for investment. This means that large multi-national companies can choose where to invest. This in turn gives companies leverage over a countries tax laws. In the UK, for example, there is much debate about how devolved authorities may change the rate of corporation tax. The theory goes that if the tax rate is lower, one can become more competitive within the global market place. At the very least, this dilutes the influence of the electorate to determine a country’s future. A worse case sees this as a way in which elected politicians are complicit in the exploitation of the work force: free on paper, but economic slaves nevertheless. The centre of power has is not easily determined. Power is not as direct as one would expect in totalitarian or slave societies. Rather, it is more subtle and manipulative.

(4) On self-help, positive thinking philosophies: If we are free thinking, self determining individuals, then it follows that we are responsible for our lot in life. If we fail, it is our fault. We have already seen, however, how power is exercised indirectly. This applies equally to gender politics as much as it does to work place dynamics. The self-help industry is based on a lie. Yes, we should take responsibility for ourselves. Only, we might continue to fight for ourselves and each other and we might still fail. That will not mean that we are to blame for our failure. Rather, we can be strong or wise enough to be worthy of the kind of society we dream about – only without any guarantee of success.